After four years of low returns, experts say 2023 is on track to be one of the worst years on record for Skeena steelhead in BC.

“The biggest factor impacting our steelhead and salmon generally speaking is climate change. It’s impacting both the marine environment and the rivers and lakes that they depend on.”

Greg Knox, Executive Director of Terrace-based SkeenaWild Conservation Trust

In the Skeena River last year, steelhead returns hit their lowest in 66 years of measuring, dropping from an average of 25,000 to 45,000 fish to just 5,280 fish. This year’s estimates are at an all-time low of 4,000.

West Coast Now spoke with local stakeholders about why steelhead are under threat and what action needs to be taken.

Ocean Heating Has Big Impacts

“The biggest factor impacting our steelhead and salmon, generally speaking, is climate change. It’s impacting both the marine environment and the rivers and lakes that they depend on,” Greg Knox, Executive Director of Terrace-based SkeenaWild Conservation Trust, told us in an interview.

Steelhead are a part of the salmon family. Specifically, they are a type of rainbow trout that travel between both freshwater and saltwater. This species can live for up to thirteen years, spending their early years in rivers before migrating to sea and then travelling upriver to spawn, often over some thousands of kilometres.

But warming temperatures in the ocean mean less nutrient-rich food for the fish. In river systems, it means more regular droughts and extreme weather events like floods, which negatively impact steelhead habitat.

Warming temperatures on their own would be bad enough, but steelhead also have to contend with disruptive logging operations, Knox said. “The logging practices in this province do not protect salmon or steelhead. They continue to log aggressively and destroy their habitats.” He also pointed to mining and urban development as other environmental concerns impacting the steelhead.

Alaska Commercial Fishery Decimating Canadian Fish Stocks

Commercial fisheries are another primary concern.

According to Knox, Southeast Alaskan fisheries are decimating steelhead populations. “They are using harmful commercial methods to kill 90% of steelhead caught in those fisheries,” he said to us.

“The numbers have been in decline for many years, and it isn’t getting better.”

Walter Joseph, Wet’suwet’en Fisheries and Wildlife Manager

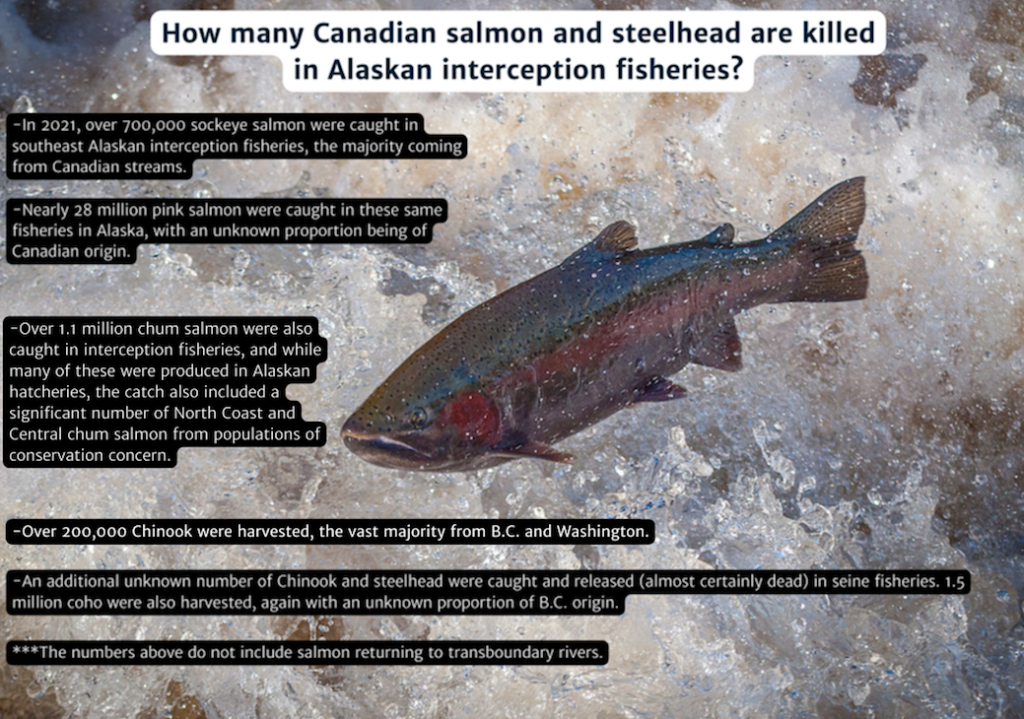

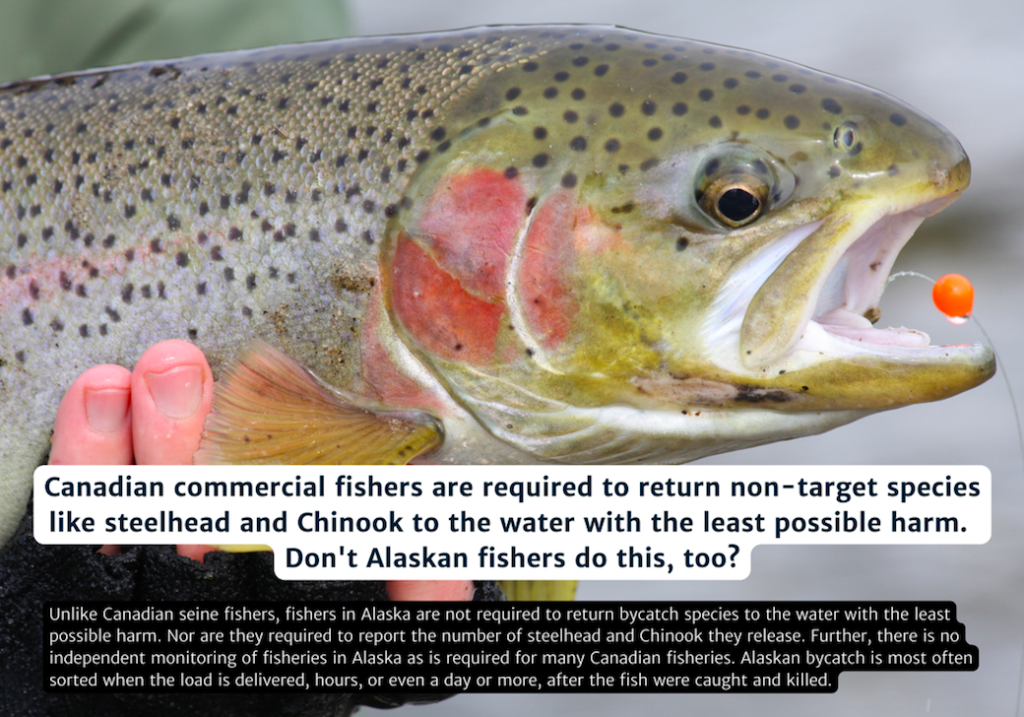

Fisheries data show that Alaska commercial fisheries targeted and harvested well over a million Canadian salmon and steelhead in 2021. Unlike Canadian fishers, Alaskans are also not required to return or report bycatch numbers. He says that Ottawa could be doing much more to protect our fish populations from Alaskan interception under the Pacific Salmon Treaty between the US and Canada.

Fisheries that use selective methods like gillnetting can have significant negative effects on steelhead. Gillnets still kill 40-60% of the steelhead even when released, said Knox.

“The numbers have been in decline for many years, and it isn’t getting better,” said Walter Joseph, Wet’suwet’en Fisheries and Wildlife Manager, talking to us about steelhead over the phone. He is also worried about Alaska’s role in the low numbers of salmon he is seeing on the water.

“I don’t think anyone has a good handle on their bycatch at all. It’s pretty hard to either prove or disprove it because Alaska doesn’t provide any numbers. When people don’t want to report, that’s an issue,” he noted.

Extinction is Economic Harm

“If you don’t look after your fishery, so it’s not going to be here next year, then you have a very short economic life. Protecting the environment is the only thing that can create good and healthy fish stocks and healthy fish stocks support the commercial fishery.”

Joy Thorkelson, UFAWU (United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union) Northern Representative and former president

People like Knox and Joseph are concerned about the dwindling numbers of spawning fish, as this means low future returns.

This also means a significant economic impact on the communities that rely on steelhead fishing. From August to October, steelhead bring money into upriver Skeena communities through sport fishing (though steelhead is strictly catch and release). This then trickles out to the surrounding tourism industry, including the lodges, tackle shops, restaurants, and hotels that boom in the late summer season.

With low steelhead returns, sport fishing businesses could soon be in trouble. Fishing tourism companies in places like Port Renfrew already are expressing concern over federally mandated limits on other types of salmon like Chinook affecting their summer profits.

Conservation Good for the Economy

“The only way to address this issue is to mandate that all fisheries are based on a conservation-first approach. This means that everyone will need to give up something in order to save Skeena steelhead and realize that the situation we now face is a direct result of putting economics before conservation,” Myles Armstead, President of the BC Federation of Fly Fishers, told us.

UFAWU (United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union) Northern Representative and former president Joy Thorkelson spoke to West Coast Now this Fall and argued that conservation is, in fact, good for the economy.

“If you don’t look after your fishery, so it’s not going to be here next year, then you have a very short economic life. Protecting the environment is the only thing that can create good and healthy fish stocks and healthy fish stocks support the commercial fishery,” Thorkelson told us.

Steelhead on the Endangered List?

Just last year, a coalition of fishery and conservation groups came together to ask the federal government to protect Fraser River steelhead trout and list it as an endangered species.

In the letter from January 2022, the authors argue that the current “situation is the most severe conservation crisis for any wild sea-run fish in British Columbia.”

Knox told us that conservation groups may soon have to undergo the process for listing Skeena steelhead under the endangered species act, as they did with Interior Fraser steelhead last year.

“It’s completely unacceptable that the provincial and federal governments are not stepping up.” Knox says that if measures are not taken soon, “our steelhead do not have a bright future.”

It’s always fair game to blame gillnetters. But study after study done by independent 3rd parties, university scientists and DFO biologists show that only between 9% and 20% of steelhead and coho caught by selective netters die. Not the unrealistic percentages claimed by ex-steelhead guide Greg Knox.

There were only 180 gillnetters this year. All trying to avoid steelhead. Far fewer than the thousands of steelhead enthusiasts who will show up to target steelhead.

But we do agree that climate change and environmental issues are creating problems for all salmonids returning to the Skeena