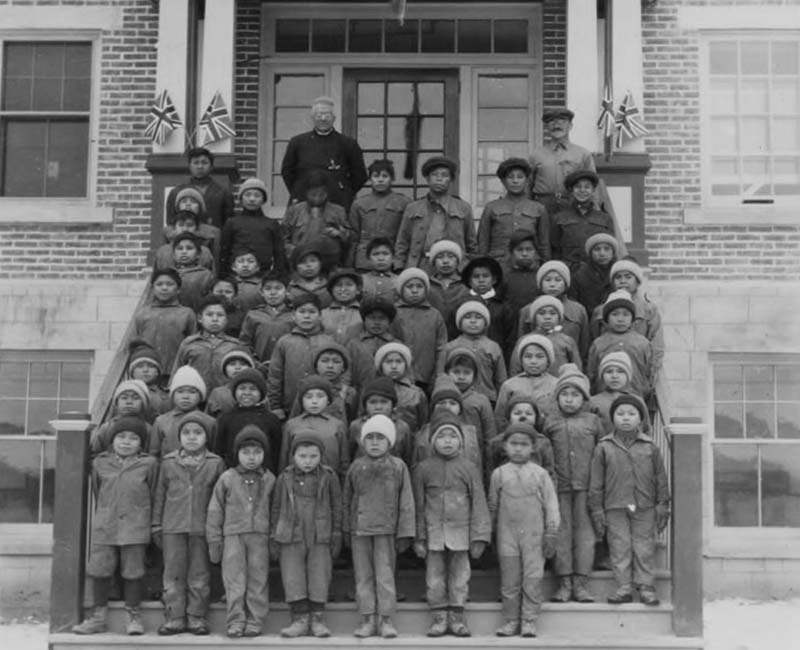

Editor’s note: Earlier this week, 160 unmarked graves were found near the site of the former residential school on Penelakut Island in B.C. In this article, Sandra Martin Harris from the Wet’suwet’en Nation of the Laksilyu, Little Frog Clan in the Skeena, explains the larger context for these ongoing terrible discoveries and what healing might look like.

Children as young as 3-years-old were taken from the warm embrace of mothers and grandmothers. If families refused, the father was often thrown in jail, or food rations or passes to leave the reserve were withheld from the family by Indian Agent R. E. Loring, who was sent to oversee First Nations in the upper Skeena in 1889. Agent Loring is an authority that many do not kindly remember, he was one of the faces of an oppressive system.

By the time children were being removed and sent to Lejac Indian Residential School, families had already lived through the burning down of cabins and buildings, being displaced, one, two or three times, every couple of years, as the land was sold out from beneath their feet, as the late Laksilyu Dini’ze Johnny David shared.

How can we gently make space to hear these difficult stories, to witness the pain and anguish and acknowledge that our shared history matters?

First Nations barely survived the epidemics of tuberculosis, smallpox and influenzas, another traumatic mass death experience. The land was sold by the provincial government, enforced by the NWMP/RCMP, Indian Agents and the local priests. Eventually, many families started to live permanently in the summer village (now one of the largest Wet’suwet’en reserves) of Kyah Wiget, or lived in Indiantown in Smithers and other places in the Bulkley Valley.

Our shared history includes many state harms, land displacement, setting up of the reserve system, Indian residential schools, Day schools, Indian hospitals, boarding schools, the child welfare Sixties Scoop, addictions and disproportionate rates of incarceration. The intergenerational hurt and pain indigenous families have carried is immense.

Our children grew up facing constant adversity. They experienced the trauma of being removed from a natural system of care, of love and connection to the Yintah (territory). They suffered malnutrition and loss of traditional foods and medicines, witnessing and experiencing abuses of all kinds, living in fear of being picked by the priests or nuns, and often the eldest children demanded to do unthinkable acts such as burying children at the residential school.

How do we heal in our families, communities and Nations from such deep soul wounds that have been here for so long?

Source: National Center for Truth and Reconciliation

If each of us could find our path through these losses, losses of family, land, language, self-love and compassion, maybe to find forgiveness of self and for others too, we may be able to heal.

Our ancestors, Creator (a higher power), and the life-giving forces, the sacredness of the Yintah, the lax yip may help us break through our silence, rage, soul wounds to release that pain, to connect us to our ancestral ways of strength, love and peace, to walk softly with self and others, with the Yintah so that we all can have a good life.

Maybe now each residential school, day school, and Indian hospital can offer a gathering, to bring our people together, to offer an apology, a meaningful one. To help us take care of the soul wounds, to find a way to heal through these generational and collective traumas so we could find a path to grow and be together, to build up compassion and empathy for each other, if needed. And for our neighbors, those that live in our Yintah, to witness, to provide support and possibly, for healing too.

It is important to understand how racist beliefs are embedded in policies, that Indigenous People are less than or are invisible. Those policies need to end, in land management, child welfare, justice, education and health systems (to name a few). Indigenous People continually confront racism, we are not safe in our most vulnerable times. These systems continue on.

Reconciliation comes in many forms, personally, within family, in community and across the Yintah. Let’s ask, what is reconciliation? And then listen, learn, reflect and come together. We collectively live together, yet we may not have had a safe space to ask what does it mean? What does it look like? How do we build respectful relations, for each of us to walk softly in our communities, to restore (or realize) balance in our families, all communities and Nations, as Murray Sinclair shared?

Elders speak of love, kindness and compassion for others, and for self. We continue to hold each other up with our songs, drumming, Yintah love, traditional medicines and stories. Our language shares our place names, connections to place, oral histories and crests. It helps sustain powerful connections to help heal our soul wounds. Connection is medicine.

Source: Gitanyow Chiefs Office

And now more than ever, there is a need for sustainable living on the Yintah, as all our grandchildren, all beings, need a healthy Yintah to grow up in. We are the land, and the land is us, is a central belief and way of being that is embedded in our Nations’ languages and cosmologies. This oneness, this connection to the sacred helps us heal, grow and thrive in our families, communities and homelands. So co ghudli, take good care. All my relations.