Vern Clayton was with his father Victor when he died in hospital in late January, nine days later his mother Verna also passed away after contracting COVID-19. When he heard his father was in critical condition and may not have long to live, Clayton raced to Mills Memorial Hospital.

“I said dad please don’t go,” Clayton said. “About eleven minutes later he passed away. I then walked over to my mom’s room, which was right beside my dad’s room. Nine days later my mom passed away, but I didn’t get to see her pass away.”

Victor, 73, and Verna, 74, had been married for 46 years and grew up in Prince Rupert, later moving to the Nass Valley. Victor was a jack of all trades, while Verna worked at canneries all her life. Working hard to provide for their children and support their community, Victor and Verna were two much-loved Nisga’a elders, and keepers of the culture.

“The elders, they’re the ones that built this place,” Clayton said. “But because of COVID-19, I can’t have a feast for my mother or my father. My mom and dad were well known; they were a big part of everyone. This whole village would be plugged with cars if we could have a memorial, but we can’t because of COVID-19.”

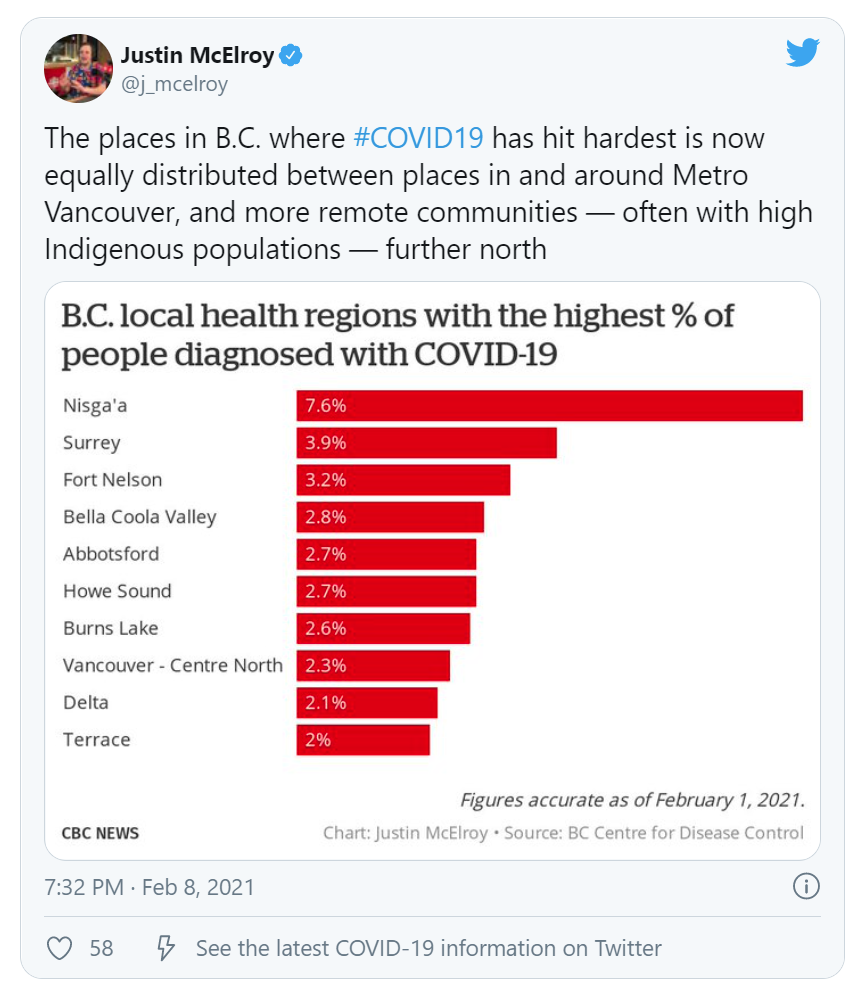

Vaccines have been rolling out across the Northwest since last month to remote and isolated First Nation communities, phase one of the Community Vaccine Rollout Plan. The goal is to ensure the most vulnerable elders are protected against COVID-19. But Nisga’a communities are still waiting to receive their first shipment of vaccines, despite having the highest rate of infection in the entire province.

The Nisga’a Nation, located just north of Terrace with four village communities, doesn’t have a firm date as to when that will happen either. They expect to see vaccines arriving soon, but the roll-out has been complicated by a national shortage of vaccines and delays in shipments from developers.

According to Tamara Guimond, the Chair of the Nisga’a Valley Health Authority, more than 1,246 people have been tested with 159 positive tests confirmed, including four deaths due to contracting the virus.

Although 144 people have now recovered and only 15 cases are still active, the situation remains dire, as the community prepares final farewells for two more cherished elders.

“No matter which way you crunch the numbers,” Guimond told Skeena Strong, “this community which treasures social gatherings is living with a significant social loss and pandemic fatigue from trying to distance socially. The end is not in sight at the moment.”

“The general initial vaccine rollout process in December and January did not allow equitable division of vaccines to people in need in the northwest, and it did not allow, specifically, vaccines to come to elderly or vulnerable Nisga’a citizens,” Guimond explained in an email to Skeena Strong.

“The Nisga’a citizens waited and watched as their neighbouring communities received vaccine protection. This situation has been perplexing and very upsetting for everyone. I continue to be concerned because we as a Nation have similar transmission, illness and rates of decline and death. Now there is a halt in vaccine production. The process is not clear to me, because we await production. The lack of vaccines necessitates the community to take heightened means to protect itself.”

About 2,000 people reside within the four Nisga’a communities. Guimond says to ensure the Nisga’a have a fighting chance to protect its citizens against COVID-19, they need 500 vaccines for elders and frontline workers, as well as an additional 300 vaccines for vulnerable populations within the Nation.

“I don’t know what other evidence can be provided that we are in need,” Guimond said. “We have illness and death. The Nation is ready to receive vaccines at a moment’s notice. I want the partnering agencies and overseers to understand we need vaccines; we are a casualty of a process that did not provide equitable access.”

Guimond is not the only one urging provincial and federal health officials to act faster to provide adequate vaccines to the Nisga’a. Ginger Gosnell-Myers grew up in the Nisga’a community of Gitlaxt’aamiks and is the first Indigenous Fellow at Simon Fraser University’s Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue. She is urging the government to send vaccines to Nisga’a communities immediately before more people contract the virus and more elders die.

“I think it’s horrible how the Nisga’a could have the highest rates of COVID in the province, be identified as being a top priority community for receiving the vaccine in the Northern Health and First Nation Health Authority plan, be hours away from the nearest hospital, and after being told they would receive 60 COVID vaccines, nothing ended up happening. No vaccines even showed up,” Gosnell-Myers said.

Although there have been major disruptions in deliveries of COVID-19 vaccines across the country due to production delays, Gosnell-Myers feels the lack of communication from government and health officials to the Nisga’a Nation as to when they will receive vaccines or as to why they were not priorities given the high positivity rates in the Nass Valley is appalling.

“Why did other urban First Nations get the vaccine before the Nisga’a?” Gosnell-Myers said. “Nobody has been able to give any answer as to why a community with the highest rate of COVID, is rural and was identified as a top community in need of the vaccine, didn’t even get it at the end of the day. Nobody wants to talk about it and I feel like it’s a little sinister to withhold this information from the Nisga’a.”

The B.C. Ministry of Health acknowledged in a statement that “reduced access to health and social services place many Indigenous people living in isolated and remote communities at higher risk of COVID-19.”

Although Phase 1 of the Community Vaccine Rollout Plan did include the Nisga’a Nation, it may still be weeks before any vaccines arrive in the Nass Valley.

“Unfortunately, over the last few weeks, production and shipping delays from the vaccine suppliers of Pfizer and Moderna has meant in the short term that there is less available vaccine to distribute in B.C. than originally planned,” according to the statement from the Ministry of Health.

“We understand many communities and individuals in B.C. are eager to receive their vaccine over the coming weeks and months. We anticipate the latest delays will only impact Phase 1 of our vaccine plan and we will be able to make up the delay in the last two weeks of February and into March.”

Still, for Vern Clayton’s mom and dad, the vaccines didn’t come soon enough.

Clayton hopes the vaccines will arrive soon and that no one else will have to experience what he and his family are going through. “COVID-19 is no joke,” he wants people to know. “It will take you out as fast as you got it.”

On Thursday, as the Clayton family prepares to bring their parents home to Nisga’a Territory, he posted on Facebook, “today is going to be the hardest thing I have to face.”

The Nation was slated to recieve 480 vaccines in the initial roll out…not 60.

Thank-you for the heads-up Brandi. We’ll call in and fact-check it tomorrow. Do you have a link to an official source?