The Canadian government’s decision to reopen the North Atlantic cod fishery to offshore draggers last year has ignited widespread criticism for prioritizing commercial interests over commitments to inshore owner-operators. Community fishers argue this decision undermines commitments to community-based owner-operators, who were assured the fishery would not be reopened to offshore draggers until the stock could sustainably support a catch of 115,000 tonnes. Instead, offshore operators were allowed back into the 2024 fishery, which had a total allowable catch (TAC) of 18,000 tonnes—a 38% increase from last year’s 12,999 tonnes allocated to the inshore stewardship fishery.

“Breaking the 115,000-tonne promise and allowing draggers back in already is going to do irreparable harm to our fishery, our coastal communities, and our province as a whole.”

Inshore Council member Glen Winslow

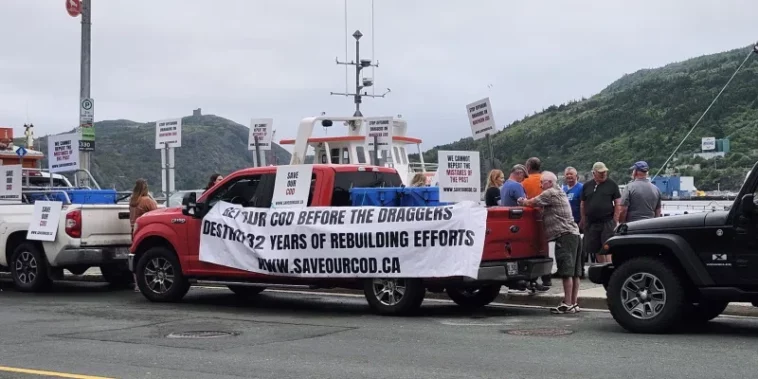

The Fish, Food and Allied Workers Union (FFAW-Unifor), which represents 10,000 owner-operators in the region, condemned the decision as a betrayal. Inshore Council member Glen Winslow said, “This fishery needs to be protected for generations to come and breaking the 115,000-tonne promise and allowing draggers back in already is going to do irreparable harm to our fishery, our coastal communities, and our province as a whole.” The reopening has also raised alarms among conservation advocates, who argue that it jeopardizes efforts to rebuild cod populations and risks repeating the mistakes that led to the catastrophic 1992 moratorium.

Local and Environmental Concerns

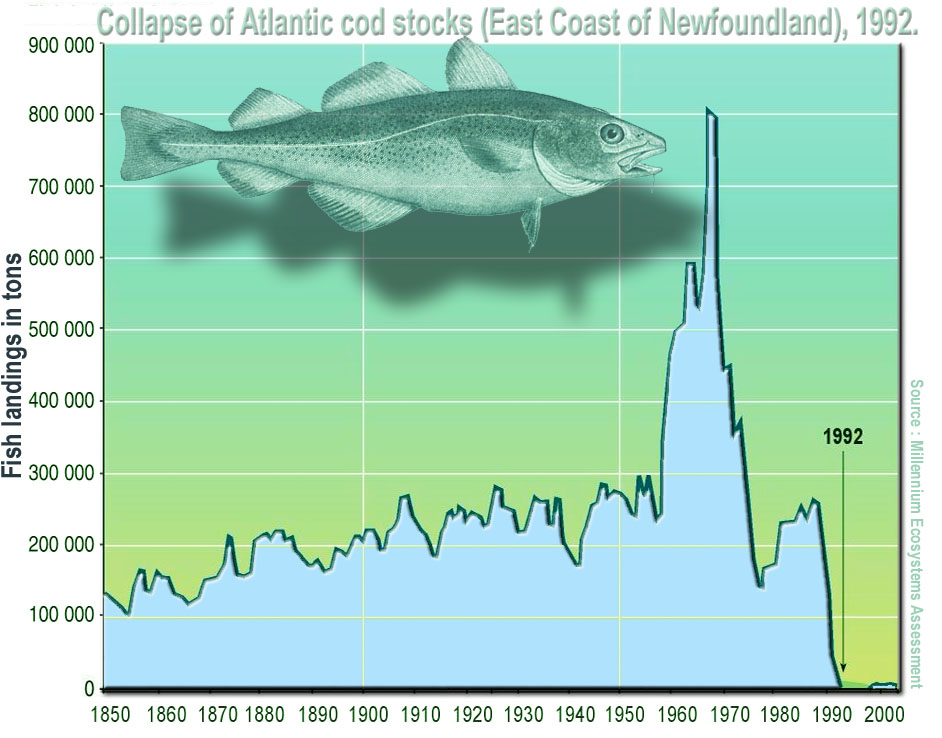

Northern cod has long been a cornerstone of Newfoundland and Labrador’s economy. At its peak in the 1960s, annual catches reached up to 800,000 tonnes, sustaining thousands of jobs in fishing and processing. However, overfishing led to a drastic collapse of the stock, prompting the federal government to impose the 1992 moratorium. This cod collapse eliminated 30,000 jobs and upended the livelihoods of entire communities.

“The inshore fleet has ample capacity to fish this stock, and breaking promises and permitting environmentally destructive draggers is counterintuitive to the Government of Canada’s mandate. As a province, we will not sit by and let it happen,” said FFAW-Unifor President Greg Pretty in a statement.

The union’s concerns are shared by others like Oceana Canada Executive Director Josh Laughren, who pointed to critical gaps in the management plan, highlighting the fragile state of capelin, the primary food source for cod.

“A major impediment to rebuilding the cod population is the lack of capelin, which is now at just nine per cent of its population size before it too collapsed, in large part due to overfishing. So, we are overfishing cod, and overfishing the main food source that can help it recover,” said Laughren in a statement.

“If the government prioritized good fisheries management, Canada’s wild fisheries could go from less than 30 percent considered healthy to more than 80 percent within 10 years, resulting in up to a million tonnes more seafood worth as much as $2 billion.”

Josh Laughren, Oceana Canada Executive Director

This echoes findings from Oceana Canada’s report Oceans of Opportunity: The Economic Case for Rebuilding Northern Cod, which stresses that rebuilding the stock to sustainable levels could support a long-term TAC of 115,000 tonnes, creating far greater economic benefits than short-term exploitation.

“Rebuilt northern cod could provide 16 times more jobs and be worth up to five times more than today,” said Laughren. “If the government prioritized good fisheries management, Canada’s wild fisheries could go from less than 30 percent considered healthy to more than 80 percent within 10 years, resulting in up to a million tonnes more seafood worth as much as $2 billion.”

Federal Fisheries Minister Ignored Scientific Advice

It has since emerged that Federal Fisheries Minister Diane Lebouthillier overrode recommendations from Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) to maintain the moratorium on the Northern cod fishery when she reopened it for commercial harvesting in June 2024. Internal briefing notes reveal that DFO staff had advised keeping the total allowable catch (TAC) at 13,000 tonnes and limiting fishing to a stewardship fishery involving inshore and Indigenous harvesters. However, political advisors within the minister’s office pushed for a TAC of 18,000 tonnes, saying that increasing the quota could be a “political victory” for Newfoundland and Labrador.

DFO staff warned that increasing the TAC and allowing offshore draggers back into the fishery heightened the risk of the cod stock returning to the “critical zone.” Although Northern cod has been classified as in the “cautious zone” since 2016 after changes to stock assessment methods, growth has stalled, and scientists remain concerned about the stock’s fragility.

“Changes that provide increased access to foreign fleets, coupled with the risk of overfishing, are an affront to the patience and commitment to stewardship demonstrated by the hardworking harvesters and processors of this province.”

Andrew Furey, Newfoundland and Labrador Premier

“I did not, and I do not believe that DFO science would recommend the policy put forth by the minister. There is a long history with this and other Canadian fisheries of politics trumping science,” said George Rose, a fisheries scientist from BC who studies cod. “Our fisheries continue to suffer.”

Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Andrew Furey called the federal government’s decision an “affront” to the province in a letter to the Fisheries Minister.

“Changes that provide increased access to foreign fleets, coupled with the risk of overfishing, are an affront to the patience and commitment to stewardship demonstrated by the hardworking harvesters and processors of this province,” said Furey in the letter that was posted to X.

For Newfoundland and Labrador, the stakes are high. FFAW-Unifor went to the courts in October 2024 to request an injunction to prevent offshore trawlers from accessing the northern cod stock. Their request was denied, and the matter will now proceed to judicial review in early 2025.

In response to a petition against the commercial reopening of the Northern cod fishery, Minister Lebouthillier said the draggers will be restricted to the regulatory area outside the Canadian 200-mile limit, and that the regulatory area is “closely monitored with vessel patrols, at-sea inspections, port inspections, aerial surveillance, and satellite vessel monitoring.”

“The Northern cod stock just entered the Cautious Zone and cannot withstand the fishing pressure of offshore draggers that fish unsustainably and during periods of pre-spawning aggregations while it continues to rebuild,” the petition said.

DFO has consistently demonstrated an inability to recognize, accept and manage commercial fishing on both coasts. It’s time for a complete overhaul of a management regime that is way past its best before date.

Let the coastal province’s take over the management of these fisheries!