Twice a day, five times a week, 10 months of the year, Sointula mariner Danni Tribe moves one of BC’s most precious cargoes.

As captain of the Spirit of Yalis, the 20-metre vessel that takes more than 70 high school students from their Alert Bay homes to their Port McNeill high school, Tribe must navigate some of the most scenic–and potentially treacherous waters–on the Coast.

But to Tribe, who has safely made the Johnstone Strait crossing for 20 years, it’s her young passengers who are “quite heroic.”

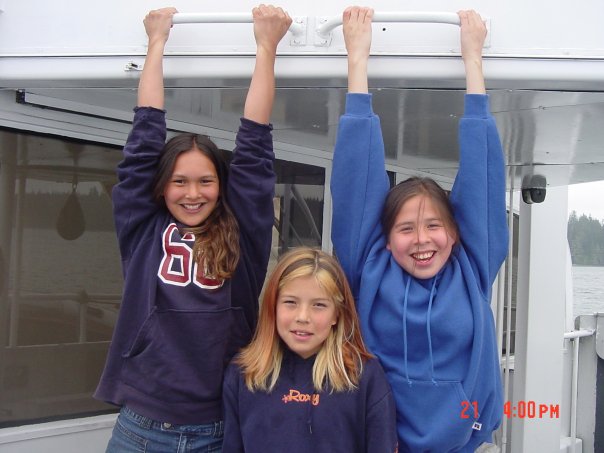

“Taking the ferry to school is fairly unique,” she says, “with 45 minutes of pretty interesting conditions, and they do it for five years. But they are so cool, so into it, doing the life jacket drills and everything else we ask them to.

“They’re good little mariners,” she adds.

Early in her career, Tribe sometimes saw the lingering trauma of residential schools and colonialism play out among her passengers. She might have to referee fights or curb vandalism. Not anymore.

She pays tribute to the hard work done by the Namgis and other First Nations in Alert Bay to heal the community: “Now they’re happy, laughing, healthy, delightful kids who laugh and tease me, sometimes in their own language.”

A 50-year resident of Sointula, Tribe started her own career on the coast as a salmon fisher on her combination boat Spar. She held leadership roles in the United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union and served for many years as a Canadian representative on the Pacific Salmon Commission.

But when fishing closures and massive restructuring knocked the legs out from under the industry, Tribe looked for other work afloat. She moved into a job with the Coast Guard, flying out to ships from Haida Gwaii to Victoria. Later came more career training, including a meteorology ticket, until she got her command endorsement and took over the helm of Spirit of Yalis.

“I make every call,” she says. “That’s what the captain does. It’s all about training. My job is all about rules and regs, tides, and currents. There’s lots of detail work, inspections, science, and math.”

Three times a day, at least, she cheques the weather and makes a decision, according to strict protocols, whether or not to sail. When the weather’s too bad, a quick Facebook post notifies parents and kids that the Yalis is staying at the dock. And if the weather worsens during the crossing, Tribe is ready to turn around.

“I love the people that forecast the weather,” Tribe says, but worries that distant decision-makers in Ottawa may cut this critical service and undermine the coastal economy in the process.

Getting the sea-time she needed to build her skills is becoming harder and harder, she says, as industries like fishing and tow-boating decline, thereby eliminating opportunities to travel the coast.

Although she’s skippered lots of whale-watching tours in the summer, “there’s not a lot of money in tourism,” especially with the North Island’s short season.

“I fear we’ve lost the culture of shipping and maritime life and I don’t see it coming back.” The fish farming sector, which supports hundreds of jobs in the North Island, is the last major source of skilled jobs on the water, and now faces its own restructuring.

Despite the challenges and responsibilities of her job, Tribe is constantly inspired by her teenage passengers.

“The kids are the excitement and the fun,” she says. “I see them 45 minutes a day, twice a day, for five years. It’s important for me that it’s a happy safe place for them on that boat.

“That’s been the joy of the job, to watch them blossom and grow up. Now I’ve got kids of the first kids I took to school –- but no grandkids, yet!”

Geoff Meggs travels the coast whenever he can and is the author of an award-winning history of the BC salmon fishery.